After the Japanese got serious about making motorcycles in the late 1960s, bikes from every country became more sophisticated, more refined, more practical, and more reliable. Back then, no American or European motorcycle company would ever admit it; fortunately, those culture wars are now behind us.

When we look back at the Japanese motorcycles that debuted between 1960 and 2000, we see several standout bikes. Not all of them were successful—or even good—but each shows us the things we like about all motorcycles, not just those from Japan. These are motorcycles that have a little something in their souls and make us proud to be riders.

In each of these eight icons, you’re likely to find something that influenced the design of the motorcycle that you’re riding today—no matter where it was built.

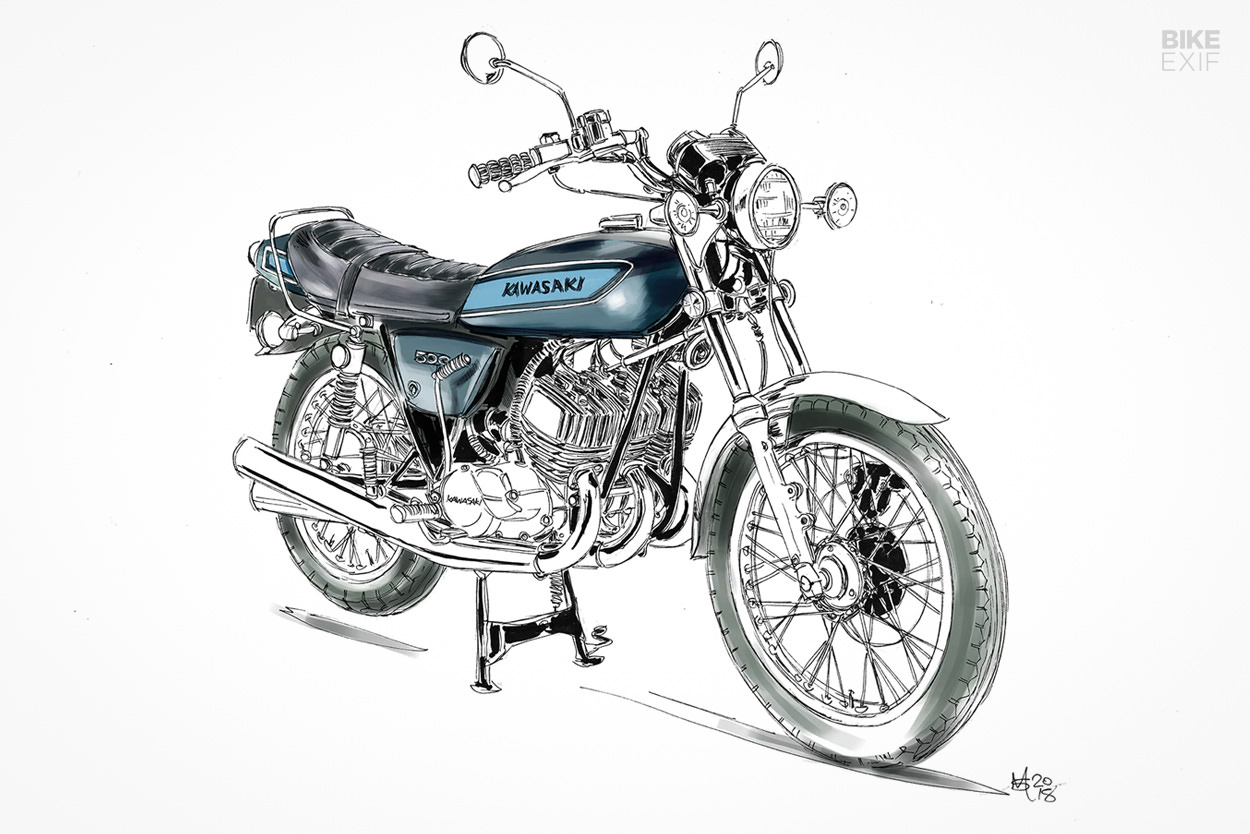

Kawasaki H1 Mach III (1968-76) When the Kawasaki H1 Mach III came to the US in 1968, the American motorcycle market was the largest in the world. If you thought of a Japanese motorcycle at the time—which you typically wouldn’t—something cheap and cheerful like the Honda CB350 came to mind. The Kawasaki H1 Mach III wasn’t cheerful; it made you hold your breath in fear.

As one of the smallest of the Japanese motorcycle makers, Kawasaki needed a marketing breakthrough and set its sights on producing a 60-horsepower engine for the street—a leap beyond what you could get from the best British bikes of the time. Kawasaki embraced the two-stroke engine concept that Ernst Degner brought to Japan from MZ’s Grand Prix bikes after defecting from East Germany in 1961.

The H1’s air-cooled, piston-port 499 cc inline-three made 60 hp at 7,500 rpm. Power from the triple and its three Mikuni carburetors came in a typical two-stroke rush, and the torque curve was, as the saying went, as steep as the back of God’s head.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t enough motorcycle around this engine to keep that power contained. The quick-steering, mild-steel frame had a short 56.3-inch wheelbase and rudimentary suspension, and with a rearward weight distribution the H1 had a distinct tendency to wheelie away from a stoplight; nearly every H1 you saw had a broken taillight.

The 384 lbs (dry) H1 Mach III turned a quarter-mile in a breathtaking 12.4 seconds on its way to a top speed of 124 mph. But hard, narrow tires, flexible wire-spoke wheels, and ineffective drum brakes contributed to wobbly handling and gave the bike a reputation as something of a widow-maker. [Kawasaki H1 customs]

Kawasaki Z1 (1972-75) As the 60s came to a close, Honda, Kawasaki, and Suzuki stopped deferring to the dominance of Harley-Davidson and started building bigger 750 cc bikes for the U.S. market. In 1969, Honda debuted its safe and sane CB750, an immensely successful motorcycle distinguished by its air-cooled, transverse inline-four engine.

In response, Kawasaki built a bike with a large-displacement, air-cooled, transverse inline-four engine that had a racing-style DOHC, eight-valve cylinder head. The prototype bike carried the code name ‘New York Steak.’ American test riders developed the new Kawasaki simply by riding it on the street as fast and as far as possible, then fixing whatever broke.

When it debuted for 1972, the Kawasaki Z1 was the motorcycle equivalent of a muscle car—powerful, mean, and more than a little crude. The 82 hp, 903 cc inline-four buzzed, and the handlebars and chassis wobbled. The tall center of gravity meant you had to seriously muscle the bike into a corner, and the wide engine’s limited ground clearance at full lean forced you to hang off to the inside instead of clinging to the saddle.

The Z1 defined the Universal Japanese Motorcycle (UJM): street bikes with transverse inline-four engines that came to dominate all categories.

In the 80s, the Z1 changed its name and incorporated new mechanical bits—a turbocharged version even appeared—and the bike earned its place in the winner’s circle of AMA Superbike racing and helped Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey become Grand Prix World Champions. Even now, the 1982-83 Kawasaki KZ1000R Eddie Lawson Replica is one of the coolest Japanese classics out there. [Kawasakie Z1 customs | Kawasaki KZ1000 customs]

Yamaha RD400 (1975-1980) There were two kinds of riders for the Yamaha RD400: the guys in Bell helmets and Bates leathers trying to become racers at the track, and the guys in polycarbonate helmets and board shorts who looked to be late for an appointment at 7-Eleven. Either way, you’d probably call them ‘punks.’

When Yamaha got itself into the motorcycle business, it created two lines of bikes: one for purebred racing bikes suited to European regulations, and the other for production-based street bikes in accordance with American racing rules.

![]()

The purebred TZ250 helped turn flat-tracker Kenny Roberts into the first American champion in Grand Prix racing, while the production-based RD400 helped turn flat-tracker Eddie Lawson into the second American Grand Prix champion.

But make no mistake: the RDs were really pocket-size bikes for punks. Yamaha’s simple-yet-refined, air-cooled, piston-port, two-stroke 399 cc vertical twin made a very usable 44 hp, and the lightweight, 352 lbs (dry) package encouraged you to ride hard and chase the top speed of about 105 mph, even if you were wearing board shorts and flip-flops.

The zippy RD400F Daytona Special appeared in 1979, and Yamaha hoped it could prolong its oil-injected two-stroke engine’s usable life in America, but the RD400 was finished in America after 1980. The water-cooled RD350LC never came to the US, because EPA standards for hydrocarbon emissions killed off two-stroke engines on the street, and 400 cc motorcycles had become stereotyped in America as cheap bikes for beginners.

Punks moved on to the 1985 Kawasaki GPZ600R Ninja, a racy middleweight bike that aroused feelings of high-speed invulnerability much like the RD. Emergency-room doctors subsequently created a new name for the consequences of this syndrome: ‘Ninja-cide.’ [Yamaha RD400 customs | Yamaha RD350 customs]

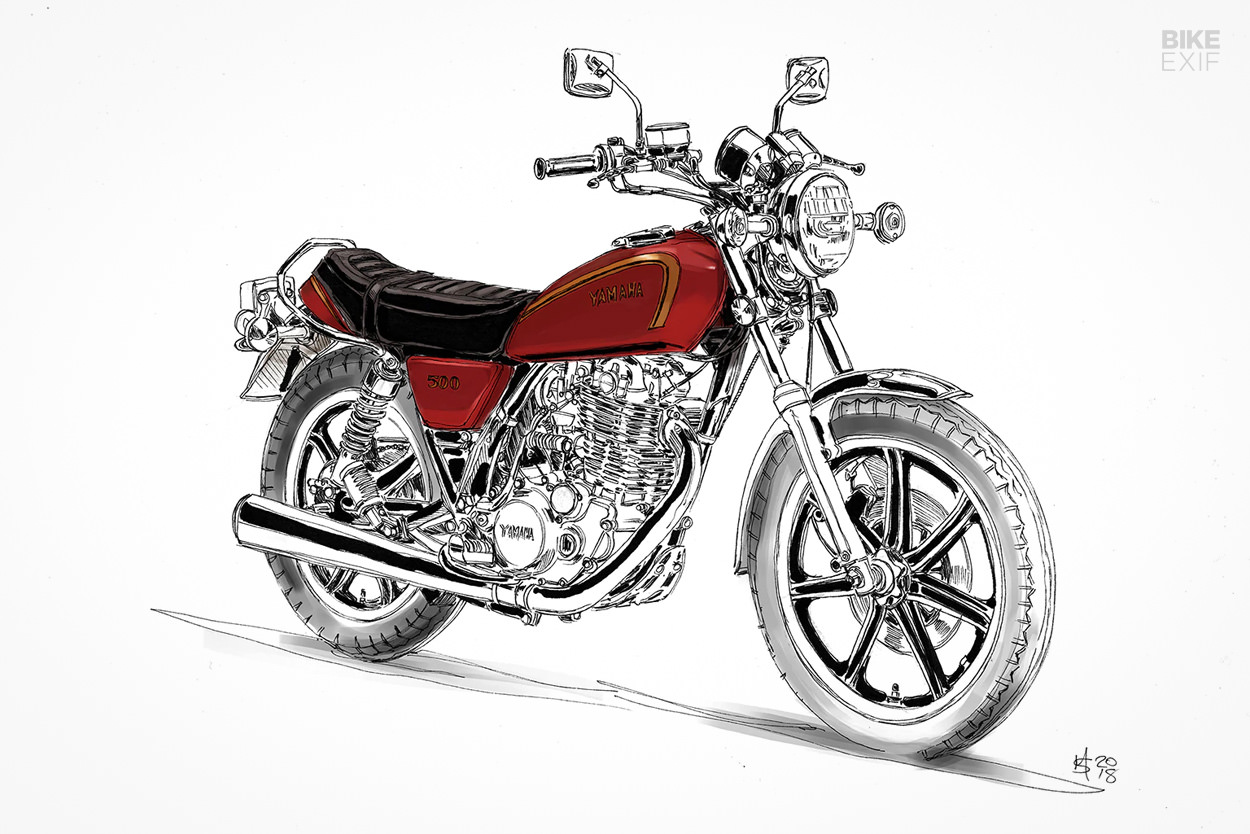

Yamaha SR500 (1978-1981) The Yamaha SR500’s mechanical simplicity and graceful styling is deeply appealing and has been since the beginning. It was plain and slim and reminded us of everything good about the traditional single-cylinder British bike, but with disc brakes and cast-aluminum wheels.

The SR500’s 499 cc SOHC engine made just 31.5 hp, which meant the 348-pound bike topped out at 90 mph, if you had the time to wait.

The engine’s deep wet sump and tall cylinder head didn’t do much for the center of gravity, but the SR500 proved easy and fun to ride. You could kick-start the engine easily enough thanks to the compression release and a clever window to indicate the compression stroke, but you couldn’t wish away the vibrations on a long ride.

The Yamaha SR500 was a wonderful bike, but it belonged back in the 1950s—just like the British singles it resembled. It was the first self-consciously retro-style bike, and it made it possible for new motorcycles to be loved simply on the basis of heritage and appearance, not just performance.

Now there are SR500s everywhere, and it’s clear that each one is cherished by its owner, who has no doubt customized it to their liking. [Yamaha SR500 customs]

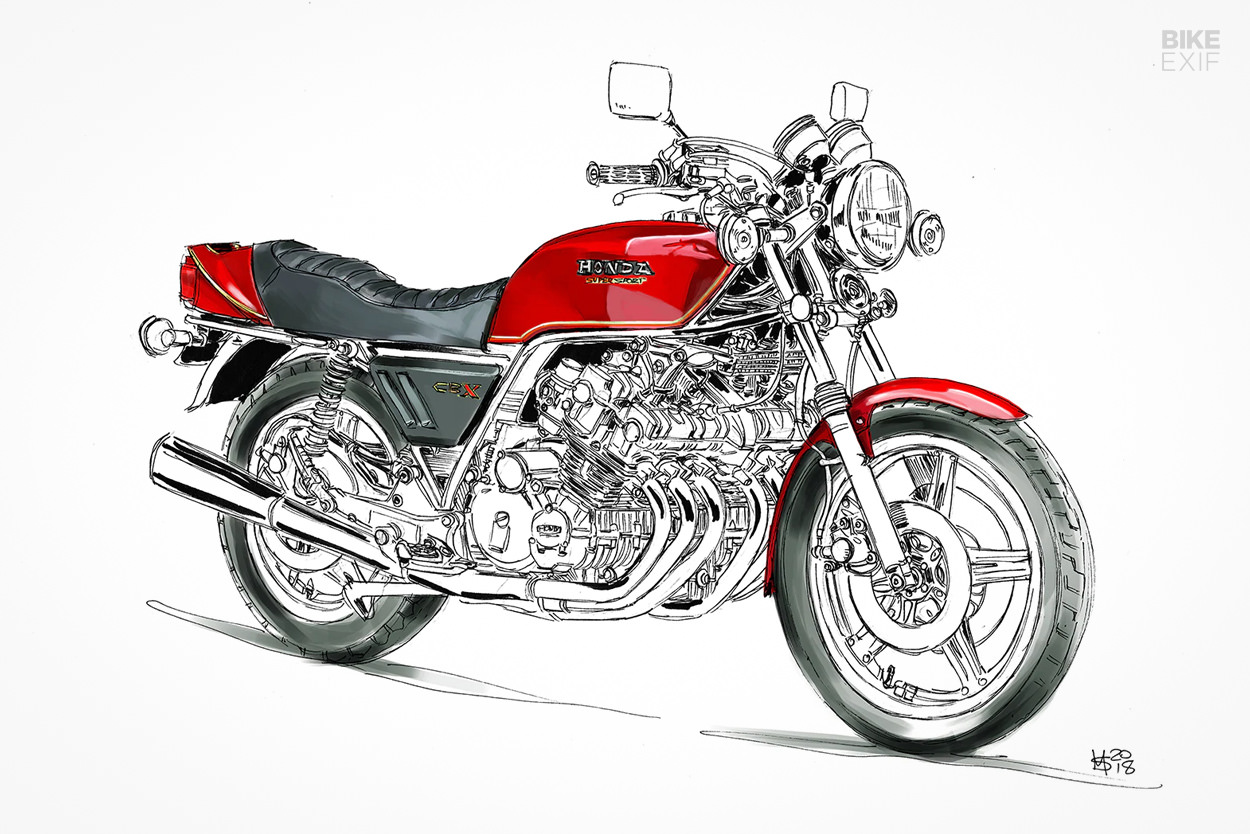

Honda CBX (1979-1982) The 1979 Honda CBX was a masterpiece, as if everything that Honda had ever learned about motorcycles had been distilled into a single bike. It’s also the poster child for everything that can be wrong-headed about Japanese motorcycle design.

As the 1970s wore on and the CB750’s contribution to the progress of motorcycle technology seemed less important, Honda assigned the creation of a new generation of bikes to Shoichiro Irimajiri, a young, optimistic engineer who had been a driving force behind the company’s Grand Prix racing bikes in the mid 60s. When American Honda’s motorcycle dealers visited Japan in late 1977 and first saw the CBX, they literally stood up and cheered.

Irimajiri stacked six cylinders in a line, used a motorsport-style central power take-off to minimize torsional loads on the crankshaft, and positioned the ignition accessories behind the crank to minimize overall width. With six smooth-acting constant-velocity carburetors and a 24-valve cylinder head, the air-cooled, 1,047 cc engine made 105 hp at 9,000 rpm; the exhaust sounded like an F-16 Fighting Falcon on the flight line.

The CBX took your breath away with its sheer audacity and 135 mph top speed, but the bike was too thirsty for fuel, too heavy for quick cornering, too hot for long-distance riding, and too expensive to repair.

Honda gave the CBX a sport-touring makeover in 1981 with a bikini fairing, saddle bags, and mono-shock rear suspension, but the model disappeared from production after 1982; it was just too much.

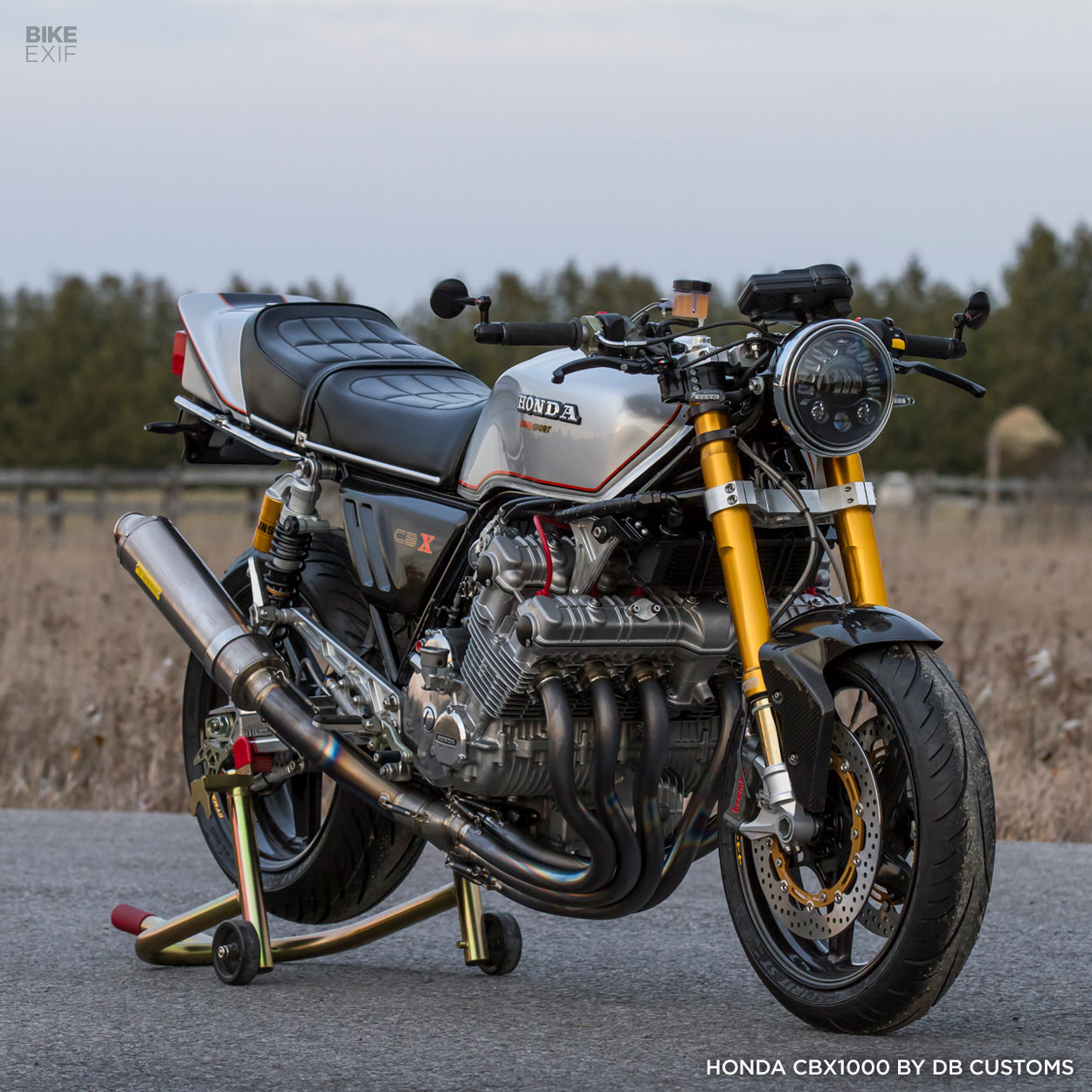

Still, the CBX served Honda well, sharing its technology with the remarkable CB750F and CB900F and encouraging even more audacious engineering, as the company adopted V-4 engines in 1982 for the Sabre and Magna. The Honda CBX is an expression of the Honda way of doing things, and is more desirable now than ever. [Honda CBX1000 customs]

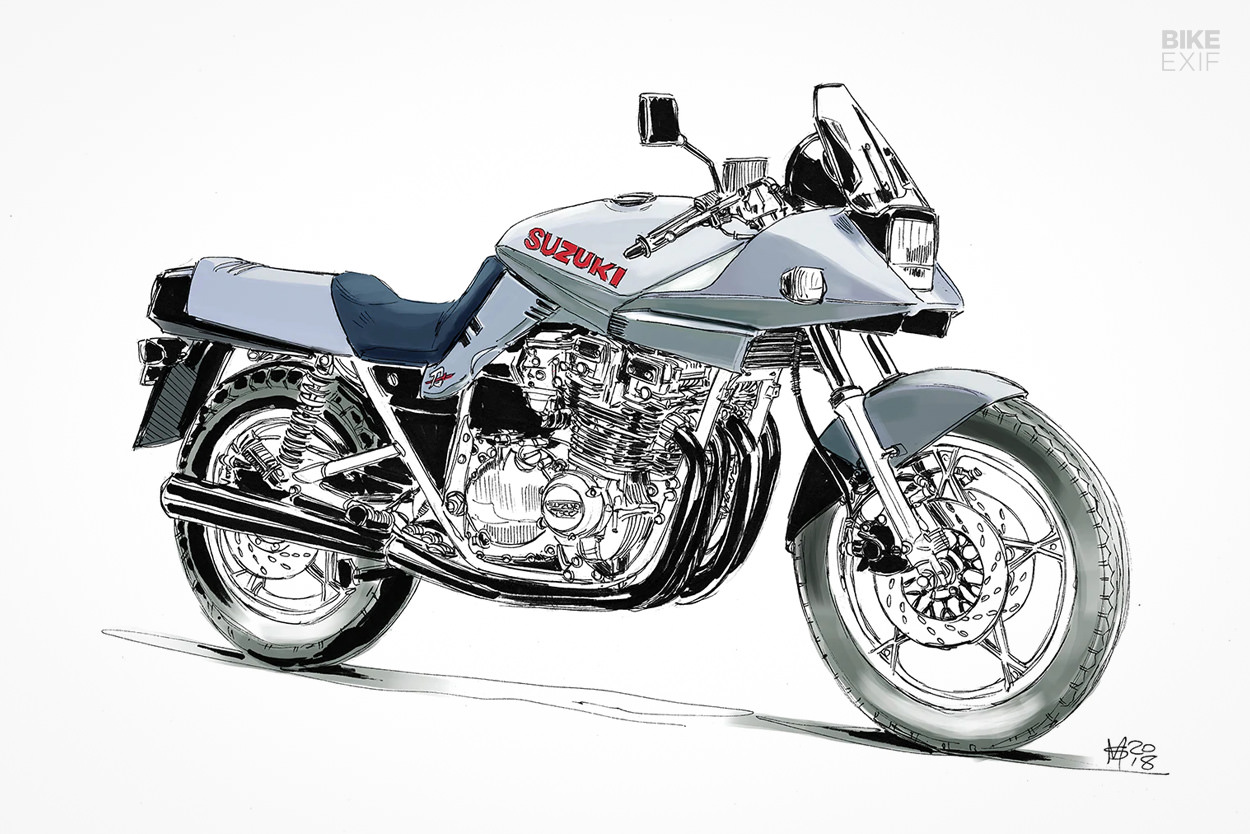

Suzuki GS1100S Katana (1981-1987) The 1981 Suzuki GS1100S Katana successfully modernized motorcycle styling. Suzuki hired Target Design—ex-BMW motorcycle design chief Hans Muth, joined by Jan Fellstrom and Hans-Georg Kasten—to create a hyper-European look that evoked not only motorcycle road racing, but also pure art.

Against all expectations, the Katana became a raging success. It helped that the motorcycle beneath that angular bodywork was very good, an evolution of the era’s best superbike, the 1978 Suzuki GS1000.

The Katana had the right kind of hardware: a structurally rigid frame with sound geometry, compliant high-quality suspension, and a powerful, yet tractable, 100-hp engine with a 16-valve cylinder head. Suzuki’s cadre of ex-GP development riders dialed in the performance on the company’s aging (but daunting) Ryuyu test track.

We now appreciate the design-conscious Katana’s accomplishments as well as the missteps it inspired, most notably the 1988 BMW K1, 1986 Ducati Paso 750, and the 1982 Honda CX500 Turbo.

![]()

The Suzuki GS1100 Katana remains contemporary, not just in its wind tunnel-tested aerodynamics and solo-rider configuration but also in its equally modern balance between street-specific refinement and track-ready performance.

And let us not forget that a couple of close encounters between a Katana and the pavement led Nick Ienatsch into writing one of the best-ever books about riding technique, Sport Riding Techniques: How To Develop Real World Skills for Speed, Safety, and Confidence on the Street and Track (2003). [Suzuki Katana customs]

Honda CR500 (1984-2001) In the 60s, a dirt bike was a scrambler, a cool name for a slow British street bike that had a high exhaust pipe, which was a feature for added ground clearance that would invariably burn your girlfriend’s leg when you gave her a ride home from high school. Then came the 70s, Bruce Brown films, and a slew of lightweight Japanese mixed-use trail bikes.

In 1974, the Honda CR250 Elsinore appeared, a two-stroke motorcycle that the legendary Soichiro Honda said he would never build. It was the first Japanese motocross bike that could beat a European motocross bike straight up.

![]()

For the next decade or so, dirt bikes were the coolest things on the planet, and the Japanese bike manufacturers conducted a war of brand superiority by introducing new technology not just every year, but every race.

When the Honda CR500 appeared in 1984, it represented everything that Honda had learned in a decade of motocross racing; it was the closest thing to your own factory-built racing bike. It was a monster, with an air-cooled, 491 cc two-stroke thumper that made 53 hp. If you pointed the CR500 in the wrong direction when the engine came on the pipe, it could kill you; along one section of the engine’s powerband, output would change by 18 hp in just 1,500 rpm.

The Honda CR500 continued in production until 2001, when a new generation of four-stroke off-road bikes superseded it. Nevertheless, the Honda CR500’s reputation is so powerful that rumors continue to suggest that Honda will revive the CR500 model as a 92-horsepower dual-sport.

For us, the Honda CR500 recalls that special time when On Any Sunday made us wish that we could ride as well as Malcolm Smith, travel the country like Mert Lawwill, and look as cool as Steve McQueen. [Honda CR500 customs]

Suzuki GSX-R750 (1985-1987) From today’s perspective, there’s not much about the Suzuki GSX-R750 to get excited about. It has a 750 cc inline-four engine, a stout frame of extruded aluminum, and wraparound, racing-style bodywork.

So, what’s the big deal? Well, this Suzuki feels so familiar because it’s the template for the modern high-performance sport bike, and much the same GSX-R that is being built today, more than 30 years on.

The GSX-R’s story really began after Kevin Schwantz took his Yoshimura-tuned GSX-R750R to second place in the 1986 Daytona 200 behind Eddie Lawson’s factory-fettled Yamaha. The first GSX-R750 weighed just 388 lbs (dry), while the air-cooled 749 cc inline-four had extremely over-square cylinder dimensions to achieve 100 hp at 10,500 rpm.

Flat-slide carburetors improved throttle response, square-section aluminum improved frame rigidity while reducing weight, double-action brake calipers improved stopping power, and 18-inch wheels and tires delivered tremendous cornering balance. You’ll recognize a similar formula in the GSX-R that you can buy today: explosively powerful engine, lightweight package, fat tires, and something for the rider to hide behind when the blast of air becomes more than the human body can withstand.

Over the past 30 years, elements of the GSX-R formula have changed—liquid cooling, fuel injection, and frame configuration—but what hasn’t changed is the basic premise that the GSX-R is a street-legal showcase of racing technology. [Suzuki GSX-R750 customs]

Words by Michael Jordan | Illustrations by Martin Squires | Article originally featured in issue 33 of Iron & Air Magazine. See it online here, or subscribe here.

![]()

from Bike EXIF https://ift.tt/E4wzMvF

No comments:

Post a Comment