It’s not everyday that you can bid on museum-caliber bikes, and Mecum’s upcoming auction at the National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa, is full of heavy hitters. The collection hits the market from the estate of John Parham, who founded J&P Cycles with his wife Jill in 1979. Having amassing one of the best private motorcycle collections in the country, John unfortunately passed away in 2017, and 300 of his bikes will be finding new homes.

With everything from road-racing Harleys, hill climb bikes and trick European racers in the collection, there’s plenty to see. Mecum is hosting the sale September 6th through the 9th, and if you’re in the midwest, do us a favor and bring one of the following bikes home—preferably the XRTT.

1971 Harley-Davidson XRTT The XRTT 750 is the most beautiful road-going Harley ever built, that’s a scientific fact. Okay, it’s more like an educated opinion backed by sources, but I welcome your challenges in the comment section. A road-racing version of the wildly successful XR750 flat tracker, the XRTT is a stunning, purpose-built piece of Milwaukee iron.

Harley’s KR750 was a dominant force in flat track racing, so why wouldn’t it work on pavement? Back in the 1960s, you could modify your KR for asphalt through HD’s parts catalog, or buy a factory-built KRTT and go racing in AMA Class C.

New rules from the AMA in 1969 leveled the playing field for British marques, and sent Harley back to the drawing board after seeing the KR750 struggle to compete. Hasty development of an XR750 racing engine based on the 900 cc Sportster, resulted in an iron-head mill that went into nuclear meltdown regularly, until a new top end was developed for ’72.

The new alloy XRTT (and some irons as well) gave European makes a run for their money in ’72, especially in the Transatlantic Match Races, but that’s another story altogether. This 1971 XRTT was piloted by Ohio’s George Roeder, who came within inches of a Grand National Championship in 1963 and 1967. The XRTT is powered by the updated alloy-head 750 engine, and is sporting a beautiful restoration with timeless HD orange and black paint and Roeder’s No. 94. Mecum estimates Lot S142 will bring between $40,000 and $48,000.

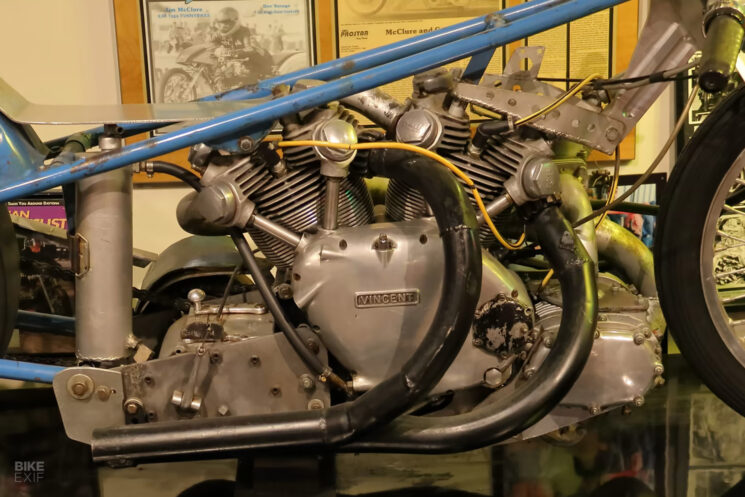

1949 Vincent Black Shadow The iconic Vincent Black Shadow is without-a-doubt one of the best motorcycles ever built. It was lightweight and well-designed with the 998 cc engine as a stressed member, and of course, it went like stink. The air-cooled, 50-degree twin was good for 55 hp, and propelled the Black Shadow to 125 mph in stock trim. Off the showroom floor or on the salt flats, the Black Shadow was indeed the world’s fastest motorcycle.

The Black Shadow would remain a speed freak favorite for years after production ended in 1955, and several American tuners perfected the bike for drag use. Minnesota-based Bill Lehmann was one of the best, and his supercharged fuel-burning Black Shadow drag bike is certainly one of the highlights of the Parham Collection.

Lehmann’s Shadow was based on a custom rigid chassis with a short Hagon inverted fork, a Harley clutch and a Burkhardt Engineering transmission. Engine output was maximized by pushing the V-twin to 1,200 cc, and installing rare Vincent Black Lightning heads. A nitromethane/alcohol blend was drawn through the SU CV carburetor and force-fed by a belt-driven supercharger from a small British car.

Rad by any definition, Lehmann’s ’49 Black Shadow is a drag racing time capsule, and one of the wildest Vincents in existence. Mecum estimates Lot F48 will sell for between $50,000 and $60,000.

1937 Brough Superior SS80 Walking out on your father’s motorcycle business to start your own right down the street is definitely a cheeky move. Even more so if you take his name, and add ‘Superior’ to the end. But if your aim is to build the best motorcycle out there, George Brough did indeed have a superior way of doing things.

Brough went out on his own in 1919, and his Brough Superior motorcycles cost nearly as much as the average person made in a year. For your sizable investment, you received a bike that was tailored to your personal taste and specification, and each Superior was fully assembled, and then disassembled for paint and plating. Brough would personally guarantee that each bike performed as it should, and in the case of the SS80, that meant it would achieve a top speed of at least 80 mph.

The SS80 was one of Brough’s earliest successes, with production starting in 1922, and ending with the outbreak of WWII in 1939. Initially, the SS80 was powered by a side-valve J.A.P. engine, and Brough became the first person to top 100 mph at Brooklands on a side-valve with one of these machines. From 1935 on, Brough used 982 cc V-twins from Matchless with modified bottom ends for the SS80.

Equipped with a brilliant alloy fuel tank with knee pads, the Brough Superior SS80 is a wonderful example of classic pre-war British bike design. Mecum expects Lot S131 from the Parham Collection to bring as much as $120,000.

1954 NSU Sportmax Sporting a massive silver-bullet fairing and a super complex little 250 engine, this 1952 NSU Sportmax may just be the most quintessentially German motorcycle ever built. Evocative of streamlined Mercedes and Auto Union race cars of the 1930s and ’40s, this NSU brings us back to an era when aerodynamics were unlimited in road racing.

BMW reigns king of the German motorcycle manufacturers today, but for many years that title belonged to NSU. Neckarsulmer Motorrad started building motorcycles in 1901, and they supplied motorcycles to the German army in World War I and II. In fact, NSU manufactured those goofy half-track bikes with a single steer wheel out front, called the Kettenkrad. In the 1930s and mid ’50s, NSU built more motorcycles than anyone in the world.

The NSU Racemax was the factory’s works machine for 125 and 250 cc road racing, instantly recognizable for its massive aluminum ‘dust bin’ fairing. The works bikes were very complicated and impractical for privateers, so NSU made a small number of Sportmax bikes available that were based on Max and Super Max models.

The 247 cc OHV four-stroke used in the Sportmax employed a pair of rods, similar to connecting rods, to operate the valvetrain—technology Bentley used in the ’20s. 250-class Sportmax bikes weren’t tuned as hot as the works bikes, but were good for as much as 20 hp.

These streamlined NSUs were quite successful in Grand Prix racing, with notable pilots like John Surtees and Mike Hailwood in the saddle, and NSU took home a World Championship in 1954. Unfortunately, the sanctioning bodies involved later banned large fairings after a bad experience with crosswinds. From then on, front fairings were not to enclose the front wheel.

The 1954 NSU Sportmax in the Parham Collection is an awesome piece of road racing history, but it’s worth noting that this particular bike is listed by the National Motorcycle Museum as a replica. As such, Mecum estimates Lot S15 will bring between $6,000 and $7,200.

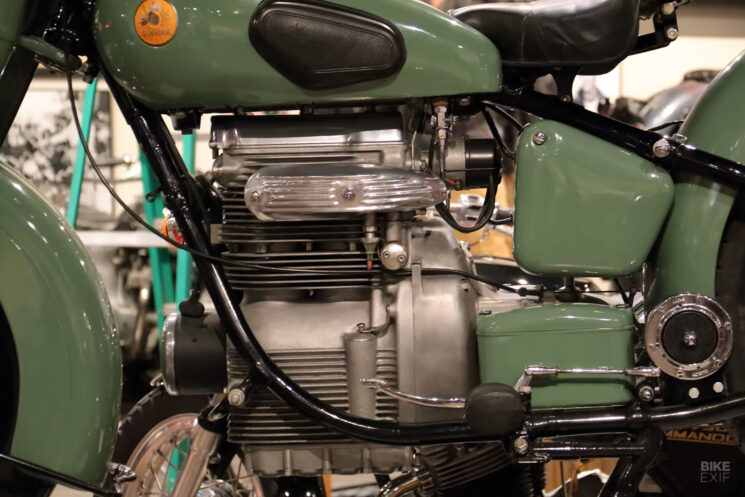

1951 Sunbeam S7 Admittedly, we find ourselves most attracted to cool customs, or bikes with notable competition history, but sometimes it’s hard to ignore a bike that’s interesting, or just plain weird. I wouldn’t call the Sunbeam S7 weird, but it’s definitely unique. I mean, look at that longitudinally-mounted twin and balloon tires?

John Marston started Sunbeam Cycles back in 1887 with a focus on high-quality bicycles. He started experimenting with motorized bicycles around 1903, but it didn’t go well, and apparently someone was actually killed. Marston dabbled with automobiles afterward (completely separate from Sunbeam Motor Car Company), but reluctantly returned to motorcycles around 1912.

Marston’s Sunbeam motorcycles fit the standard for British bike designs of the era, and boasted modest performance (understandably so), and Marston marketed his bikes as ‘The Gentleman’s Machine.’ Marston passed away in 1918, but the production of Sunbeam motorcycles continued on.

Sunbeam is best known for its S models, which were manufactured between 1949 and 1956, and that’s where things start to get a bit strange. Sunbeam was acquired by BSA, and BSA had received the design of the BMW R75 in reparations after WWII. But the Brits were worried about the bike looking too German, so the boxer had to go.

A longitudinally-mounted 500 cc twin took its place, and propelled the S7 via shaft drive. Early bikes suffered severely from engine vibration, and the bronze worm gears in the shaft drive could strip from nothing more than excessive throttle. Sunbeam’s solution was nothing more than detuning the engine!

Despite these design faults, the early S7 model commands a premium over the S7 Deluxe and S8 models today. If the S7 from the Parham Collection is indeed one of these early models, Lot F51 could be a bargain at the estimated $7,000 to $8,400. [Mecum]

from Bike EXIF https://ift.tt/c8EdzaI

No comments:

Post a Comment