If you’re a student of Ducati racing history, you’ll know the Supermono—one of the most tingle-inducing singles of all time. In the mid-90s, just 65 of the light and compact racebikes were built, shot through with carbon fiber and draped with elegant bodywork designed by Pierre Terblanche.

We’ve often wondered what a modern-day Supermono would look like, and that question has just been answered by Chris Cosentino of New Jersey. It’s called the Hypermono, and it’s a remarkable feat of engineering.

Not many workshops can list projects for NASA and Victoria’s Secret on their CVs, but Cosentino Engineering is one of them. Chris has been machining, welding, and fabricating stuff for more than three decades, and now leads a team of likeminded souls in a 4,000 square foot facility crammed with both old and new school tech.

The Hypermono is the culmination of 25 years of racetrack R&D, with a goal of creating the lightest and most powerful single-cylinder race bike possible. It’s a virtually ground-up build, with a custom frame, engine and suspension setup—plus 3D printed bodywork.

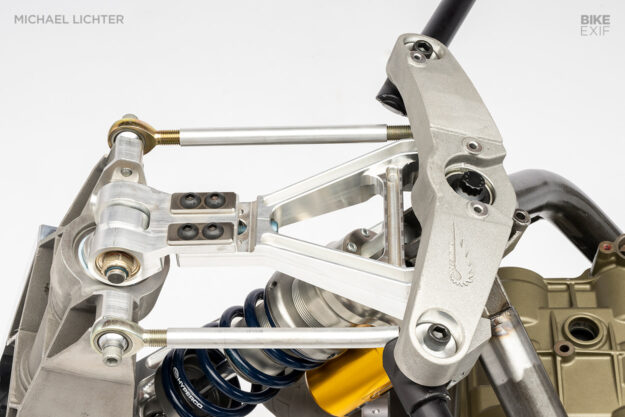

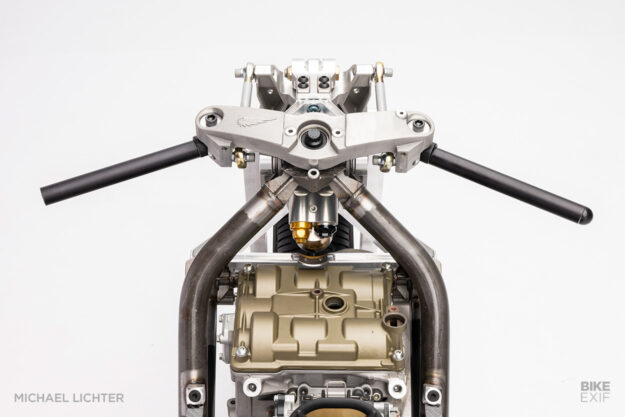

“A list of mods is answered by ‘nearly everything’,” Chris tells us. “The project started as an exploration of alternate front suspensions—inspired by the Britten, and informed by the writing of Tony Foale.”

Chris has a lot of experience in this field. In the early 2000s he raced a Honda RS125, built a bike with a ‘Funny Front End’ frame, and grafted a Ducati 999R cylinder head onto Rotax crankcases. But the 2008 economic downturn killed the market for expensive custom race bikes and put Cosentino Engineering on life support.

Ten years or so later, after a business recovery and abstinence on the racing front, Chris got the racing itch again. And he noticed that Kramer was selling race singles with some success.

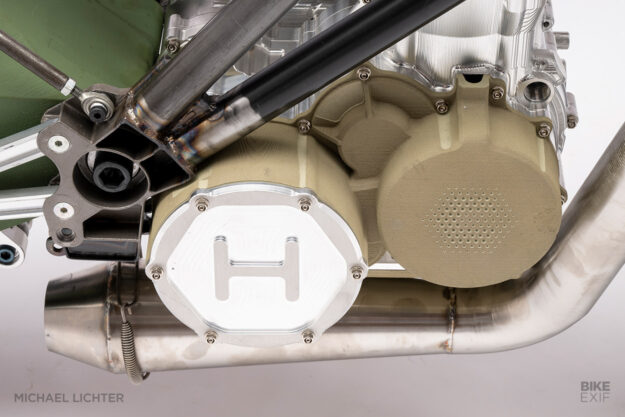

With a little help from renowned petrol head Jamie Waters, Chris kicked off the Hypermono project by designing a new bottom end to fit a Ducati Panigale 1199 cylinder head. Machined out of 4340 alloy billet is a reverse rotation crankshaft and counterbalance shaft, enclosed within billet aluminum crankcases. Capacity is 600 cc and there’s even an electric start.

The side covers and oil sump are sand cast magnesium, and the 62 mm exhaust has been printed using cutting-edge direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) equipment.

The electronics are equally sophisticated, built around a Marelli REX-140 ECU/data logger—the official engine control unit for the Moto2 Championship in the 2019-2021 seasons. There’s also a combined GPS/Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), and Chris describes the setup as “MotoGP level software with rider aids.”

The powerplant is snuck into a frame welded up from 4130 steel tube, with lugs that have been investment cast from 3D printed surrounds.

Tony Foale’s influence is especially obvious in the front end. It’s a linkage suspension with intricately engineered uprights, pivoted supporting arms and a direct-acting custom Öhlins TTX shock. The concept may be somewhat vintage, but the execution is thoroughly modern.

The rear end is dominated by a one-piece magnesium swingarm, sand cast by Yankee Casting. “The mold used for printing was directly 3D printed in sand by Humtown, so no pattern was necessary,” says Chris. Adjustable chain idlers make it possible to dial out on-throttle squat and damping is handled by another custom Öhlins TTX shock.

To keep weight down, the rims are five-spoke carbon fiber units from BST. Braking is handled by Brembo billet calipers with custom Braketech cast iron rotors.

“I’m now nearing completion of this build,” says Chris. “It incorporates everything I’ve learned from racing for the past 25 years into a new, clean, and elegant design. I was lucky enough to have Nick Graveley of ClayMoto offer to design custom bodywork, which looks absolutely awesome.”

Chris is currently 3D printing a test set of that bodywork—on a 3D printer he made himself for this task. And once the shapes are optimized, complete with cooling ducts and aerodynamic wings, he’ll use the printer to create parts that will be used as patterns for carbon fiber layup.

That’s the race side sorted, but there’s another development we’re even more intrigued by: Chris has built a bobber version of this bike too, and is looking at doing a short production run.

“I recently showed the unfinished bike at the One Moto show and it had a great reception in its naked form. That led me to investigate the possibility of offering them for street use, and I am now a registered vehicle manufacturer under Cosentino Motor Company, LLC,” he says.

“So street sales are a real possibility. That would create a nice wave to ride before my next project is finished: a battery electric version of the same rolling chassis, intended for higher volume street sales.”

Given Cosentino’s reputation for top-drawer engineering, that sounds like a very enticing prospect indeed.

Cosentino Engineering | Images by Michael Lichter Photography

from Bike EXIF https://ift.tt/5MXZNCp

No comments:

Post a Comment