The Kawasaki Zephyr 750 is one of those under-the-radar bikes that deserves a higher profile. It played a big part in kickstarting the retro boom in Europe in the 90s, but mysteriously fell flat in the USA—despite outclassing the Honda CB750 Nighthawk on almost every front.

“The stable, no-surprises Zephyr works like a standard is supposed to,” said Cycle World at the time. “We can’t imagine why this bike isn’t selling.”

The Zephyr 750 has plenty of fans amongst riders in the UK, and two of those fans are Linda and Paul of November Customs. They’re based in a small town in the northeast of England, and run the business out of a tiny wooden shed in their back yard. It’s slightly smaller than a shipping container.

“We’ve got a Bridgeport miller in there, a hydraulic bike bench, a small lathe, MIG and TIG welders, and tools for sheet metal work,” says Paul. “The bed of the miller also acts as a work bench for pipe benders, sheet rollers and such like!”

Despite the cramped surroundings, business is thriving. Linda runs the company, while Paul chips in after-hours. This 1991 Zephyr cafe racer is Linda’s personal ride—designed and built to suit her excellent taste.

Like most November builds, the Kawasaki arrived as a partly finished project bike with low mileage. And the first change, surprisingly, was to a tubular Honda CB900 swingarm, to suit the frame better. The shocks are YSS: “We went for the ones without the piggy back reservoir, for a more simple look,” says Paul.

Then a complete Ducati 848 front end was grafted on, using a Ducati yokes, along with clip-ons from a Ducati 748. But the original Zephyr wheels then looked wrong at this point, so November tracked down a set of nearly new Triumph Thruxton 1200 rims.

New Brembo discs were fitted—the front discs being from a Triumph 675, which bolted straight on. Aprilia calipers were used as they had the same bolt spacing as the Ducati forks.

“Using the Ducati forks, Triumph wheel and Aprilia calipers, nothing lined up,” Paul reports. “We worked out that if we machined 4.5mm from each side of the front hub, the discs would line up with the calipers. Problem sorted!”

And those linkages behind the forks? It’s a mechanical anti-dive system. “This isn’t the first one we’ve done, and even though it was never the best idea first time round, we love the mechanical side of it,” says Paul.

“We also get people asking why only one side? When it was first done, manufacturers used single- or dual-piston calipers. But we’re using Brembo four-pots so having anti dive on both sides would just lock the front end completely. And hitting a bump would have the bike pogoing all over the place. I’ve no doubt we’ll get haters talking about it, but we like it—and it does actually work.”

The rear wheel went straight in, with the front and rear sprockets lining up perfectly. A Brembo twin-piston caliper was then hung on a one-off hanger made to suit. (“It’s a very snug fit but works brilliantly.)”

Brembo RCS radial master cylinders were used, keeping the Brembo theme going for the brake set up.

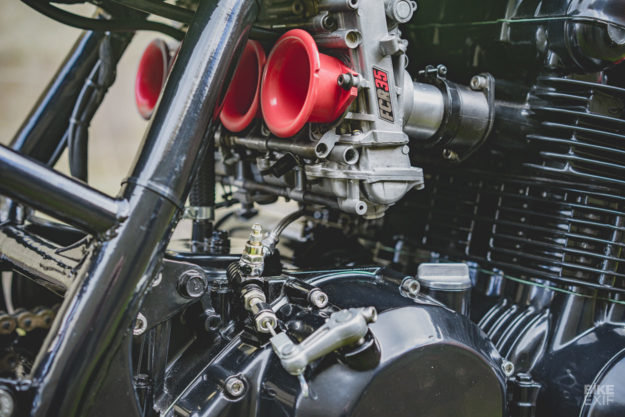

Then Linda and Paul stripped the air-cooled DOHC four, rebuilt it, and powder coated the cases black. The clutch has been converted to a hydraulic setup and the stock Keihin 32mm carbs were swapped out for FCR35 flatsides and a quick action throttle. (“Had to import them from Japan though, but worth every penny.”)

The identity of the exhaust headers is lost in the mists of time, but the intermediary pipe and muffler have been lifted from a BMW S1000R and made to fit with a little jiggery-pokery.

Next came the bodywork. “We’ve always wanted to do a monocoque setup with an endurance-type fuel cap,” Paul explains. “So we cut off the original subframe and made a new one to suit. This also houses the electrics in a tray under the seat.”

The tank is the original—but heavily cut and modified, and with the seam now extending into the seat unit. Then November welded a temporary frame to the headstock and used that to help shape and build the fairing.

“This took a couple of days of cutting and hammering on a leather bag, but we got there eventually,” says Paul. “When it came to cutting off that temporary frame, we had fingers, arms, legs and toes crossed that nothing moved or dropped off!”

The screen was lying around the shop, but turned out to be a good fit after a session with the angle grinder. It’s attached using endurance-style quick release pins.

The tailpiece houses a small lithium ion battery, and like the rest of the bodywork, is steel. “We get people tapping on it all the time to see if it’s steel. We don’t mind though, as people then go, ‘Oh my, yes it’s steel!’”

“Taking the bodywork off isn’t a five-minute job,” Paul warns. “So I’ve put the fuse box between the top frame rails under the rear of the tank, where it’s accessible with the bodywork on. It means getting down on your knees to check the fuses, but that’s a small price to pay.”

To finish the Zephyr 750 off, Linda and Paul rewired it, installed LED lights in custom billet surrounds, and drilled and lock-wired many of the bolts. The delicious Kawasaki green paint was laid on and the bike dyno’d to get the flatslides into optimum tune.

It just goes to show that you don’t need a workshop the size of an aircraft hangar to build a great bike.

And if you’re in the US, you can still get a mint Zephyr for under $3,000. Anyone starting to get some ideas..?

November Customs | Instagram | Images by Tony Jacobs

from Bike EXIF http://bit.ly/2E0IOpl

No comments:

Post a Comment